Ed Bookman

I’d like to tell the story of a man I respect and call a friend, Ed Bookman. It’s a longer story, but

truly one well worth the read.

At the young age of 19, Ed "Skip" Bookman, had the world at his fingertips. The year was 1965. He

recently started a new full-time job, had a brand-new girlfriend and brand-new car.

Ed arrived home from work one evening as his mother carefully pushed a letter across the

kitchen table to him. It began: “Order To Report For Induction” From the President of the United

States.”

"I didn’t know anything about Vietnam," Ed explains. " I didn’t know what it was or even where it was."

This isn’t a story about war. This is a story about experiencing war and about the obligation to

serve. About how easy it is to listen to the facts or read statistics of wars we’re taught in school,

but never truly understanding the true life of a soldier. Ed’s story is one of strength,

determination, and even some defiance. And it needs to be told.

Ed respected his drafting request, had his physical and reported for duty at 6:15 a.m. on Duke

Street in Lancaster that year. His journey began with six to eight weeks of boot camp, then

returned home for two weeks of leave. Afterwards, he headed to Fort Lewis for advanced

infantry training and jungle training. After nine months, he began his arduous journey to

Vietnam.

Over 5,000 soldiers packed into a WW II troop ship, which left from Puget Sound in Washington

State. The 16-day “cruise” turned into 22 days as the craft hit a typhoon on its way. Ed was one

of the lucky ones, who only experienced sea sickness the first day. Others spent the entire time

sick until they finally stepped foot on land. The food was terrible, the space limited. While the

ship fought through the typhoon, the men were forced to stay in close-quarter bunks that were

four tall, with inches of space between.

After 22 excruciating days, the soldiers met the shore of Vietnam.

“As soon as you walked into that air. And that heat hits you. And the smell. It’s something you

never forgot and never want to smell again,” Ed tells me.

All 5,000 men boarded landing crafts, which took them to the beach. The sides dropped and the

soldiers walked into knee-deep water, fighting through water with duffle bags to reach the beach.

The fourth division band was playing on arrival and the brigadier general and officers welcomed

them.

“It was like a circus,” adds Ed with some stress in his voice. “Then they put us on trucks and

took us to base. And we stayed there for about a week and then we started maneuvers and were

out on the field for a whole year.”

Ed’s mom, like thousands of other parents, worried about his safety every minute of the day and

for peace of mind, she wrote her only child every single day.

“My mom wrote everything down in a book. When I was on leave, when I called home, she

wrote it all down. I called home twice a week when I was in the states. She always told me, ‘I

don’t care what it costs, call home.’ And when I got home, I saw some of those bills were $85.

Which was a lot of money. I had to call collect. Back then, that was expensive.”

“She was concerned about me,” he continued. “I could tell. I had a Kodak instant camera with a

film cartridge. She would send me rolls of film, I’d send the roll of film back and she would

develop them and put them in an album. Someone once asked me why I was smiling in all of

them. Even the one with the dead guy. I did it for her. I didn’t want to worry or upset her.”

After leaving for Vietnam, Ed was only able to call home twice. His letters from his mom were

numbered so he knew what order to read them, because mail was sometimes few and far

between. She wrote about home, about the neighbors, what was for sale at the store, anything to

help normalize Ed’s time on the frontlines of a war zone. Others received newspapers from home

or other trinkets, a small token of hope and encouragement to let each soldier know people were

thinking of them at home.

“If you didn’t get mail, you shared,” Ed continues. “Just to feel like you’re back at home. Being

away like that is a bitch. And you just hope you would get back home.”

As Ed showed me his tags, I wondered if he was ever scared. Or homesick. Or sad. Or felt

defeated.

“You couldn’t think about being scared. Yeah, you are. But you can’t think about it. If you got

shot at and hesitated, you died. You can be scared tomorrow. It’s instinct. As soon as something

happens, you move, you don’t wait for someone to tell you. But if someone told you they

weren’t scared, they were lying.”

Let’s forget about the fact that these men didn’t eat properly and slept in fields in horrid

temperatures and other conditions. Or didn’t shower for weeks and months at a time. Or had to

carry heavy duffle bags and armory. And burn the mail sent from loved ones so they didn’t have

to carry additional weight. They were shot at, without notice and sometimes without protection. Ed

explained to me the first time he experienced being ambushed with shots inches away from him.

They stopped for lunch and some rest one day. Everyone took off backpacks and shirts, trying to

grab just a few short minutes of rest.

“All of the sudden all hell breaks loose,” Ed tells me. “Machine gun rounds going off. Everyone

grabbed their helmet. The fire was from the other side. They were firing at guys on the others

side. They weren’t aiming at us, they ambushed another group. We didn’t know how many were

there, where they were. You try to know what’s around. And make sure no one is shooting in

front of you. And I was laying down, it was a big open field, there was no place to hide. As I was

crawling there were rounds all over. And it was over in 15 minutes. They didn’t hit us. And then

they left. That pissed me off.”

When Ed received orders to return home, he grabbed his pack, boarded a helicopter, turned in

weapons and gear and began the trip to the states, with other soldiers, and headed home.

“You could believe it but you couldn’t believe it,” Ed explains. “And as soon as that plane lifted

off, everybody yelled. You couldn’t hear anything.”

Ed’s long trip home finally landed him at the Philadelphia airport where his parents met him.

They hugged and kissed and shared some tears together and began their way back to Lancaster.

“We got in the car and headed home. No one said a word. That’s the way it was. No one talked

about it. I lived on South Prince in Lancaster. There was a big banner that read ‘Welcome home,

Skip.’ That was my welcome home. That was it. I talked to my parents a little and went to bed. I

think I slept for five days. The next two weeks, I didn’t do anything, but we didn’t talk about

Vietnam. I went back to my old job and that was it. End of story. But that sign, for some reason,

makes me so emotional sometimes when I talk about it.”

Almost one million men served in Vietnam from 1964 to 1975. There were about 650,000 men

drafted. Many lost their lives in combat or to Agent Orange. Over 100,000 are still missing in

action. Remains are still being found and brought home to families. About 79 Lancaster residents

were killed in Vietnam with 17 from McCaskey, Ed’s alma mater.

There were 200,000 men who fled to Canada to avoid the draft. There were protestors who spit

in the faces of soldiers returning home. For many Vietnam Veterans, their return was not a happy

one and there are many who suffer from post traumatic stress disorder.

“I’m bitter today about being drafted,” Ed continues. “I was out of high school a year and a half.

I had the world by the butt. And then it was gone. And I can never get it back. It was the luck of

the draw. I’d never go back. I hated the service. I didn’t like it. I did what I was told to do, I kept

my mouth shut. I did my year and got the hell out and don’t look back. I was proud I served. And

I’m prouder today than ever.”

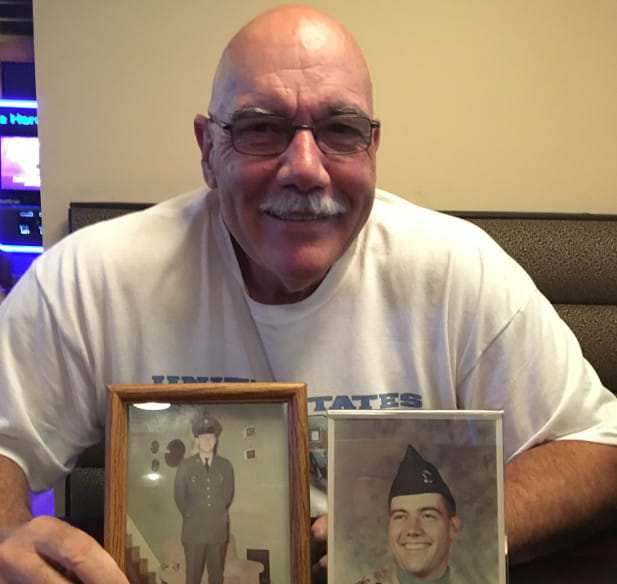

Today, Ed is a happily married retired man living in Lancaster. He began serving in the Honor

Guard and has served at over 500 funerals of veterans. He speaks at local high schools about his

experiences, speaking to over 6,000 students since he began. He takes with him his draft letter,

his pictures, his tags, and memories. What Ed did back in the sixties and what he does today is a

testament to us all.

What I wanted to do with this article, was to understand. And I hope to continue to reflect and

value the individuals I come across and their trials and tribulations. Ed Bookman was just a start.

As Aristotle wrote “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without

accepting it.”

Leave us a comment, tell us about someone you learned about and respect. What made someone

stand out to you?

Story Highlights

- We’re talking about Vietnam

- Let’s understand our soldiers

- Drafting and education go a long way

Related Stories

- Furloughed, Conversation with my Father

- Covid 19 Virus

- When Jackson Met Jess

- An Interview with Jess King

- Weight Gain - Shaun T.

- Helping to Fight Congenital Heart Disease

- In Guns We Trust

- The Elusive Balance

- Living in a Technology World

- The Joys of Home Ownership

- Reflections on Aging

- Lancaster Pride Fest

- Birthday Project 2017

- Womens March 2017

- So you want a revolution